CITA ESTE TRABAJO

Berdugo Hurtado F. Management of kidney failure in patients with advanced chronic liver disease. RAPD 2025;48(5):175-189. DOI: 10.37352/2025485.2

Introduction

Acute kidney injury (AKI) is one of the most common complications in patients with advanced chronic liver disease (ACLD), with a variable prevalence of between 27% and 53% of hospitalized patients with decompensated ACLD[1]. In general, AKI is associated with a high morbidity and mortality rate and a higher incidence of chronic kidney disease after liver transplantation. Progression to advanced stages of AKI portends a worse prognosis in cirrhotic patients[2],[3]. In 2012, the Acute Disease Quality Initiative (ADQI) and the International Club of Ascites (ICA) promulgated new diagnostic criteria for AKI[4]; which were recently revised in 2023-24 given the significant advances made in this field over the last decade[5].

Definitions and classification

Currently, we define AKI as an increase in serum creatinine (sCr) ≥ 0.3 mg/dL in less than 48 hours or a percentage increase in sCr ≥ 50% from baseline in the last 7 days[6],[7]. As a new criterion in the latest ADQI and ICA consensus, it is proposed to include urine output (UO) ≤ 0.5 ml/kg for ≥ 6 hours as a criterion for AKI, taking into account the difficulty of closely monitoring it and that it may be low in the initial hours of follow-up of these patients with ACLD. Even so, we emphasize the introduction of this new criterion, not so much as a diagnostic criterion, but as a criterion to be taken into account in order to detect patients with AKI earlier and thus act promptly[5],[8]. In turn, AKI is staged in different degrees according to the percentage increase in sCr from baseline, which we break down in Table 1 below.

Table 1

Definitions and criteria for kidney disease according to the ADQI-ICA consensus.

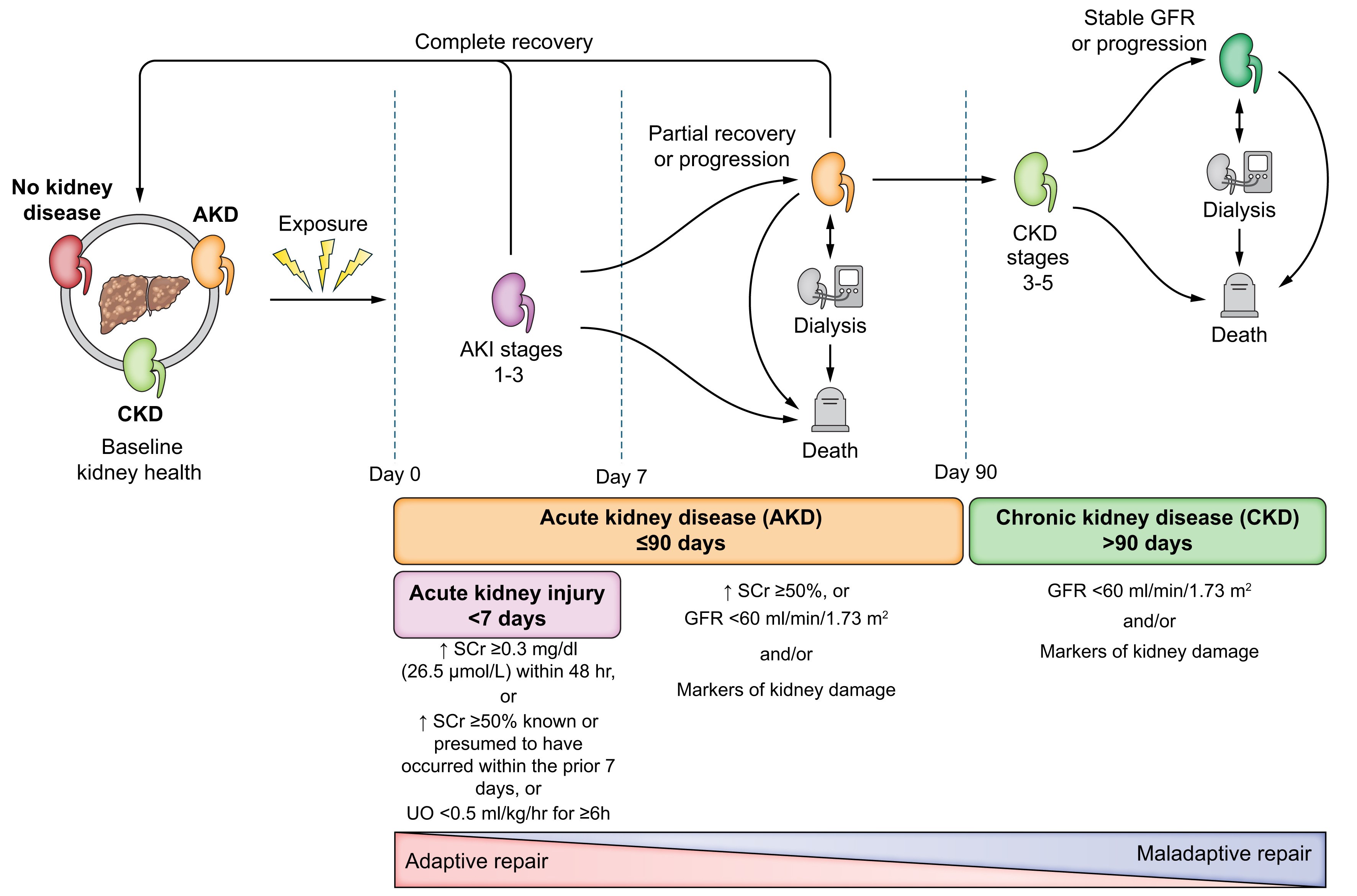

The ADQI-ICA5 consensus recommends using the lowest stable sCr value obtained in the last 3 months as the baseline value, or, if this is not possible, the lowest stable value up to 12 months prior. Monitoring the baseline sCr value will allow us to distinguish between AKI, acute kidney disease (AKD), and chronic kidney disease (CKD) (Table 1, Figure 1)[5]-[7],[9]:

Figure 1

Progression of kidney dysfunction in patients with advanced chronic liver disease. Extracted from: Nadim MK, Kellum JA, Fomi L, et al. Acute kidney injury in patients with cirrhosis: Acute Disease Quality Initiative (ADQI) and International Club of Ascites (ICA) joint multidisciplinary consensus meeting. J Hepatol. 2024; 81: 163-83.

▪ Acute kidney disease (AKD): glomerular filtration rate (GFR) < 60 ml/min/1.73m2 or percentage increase in sCr ≥ 50% (1.5-2 times) from baseline in ≤ 3 months. Following the definition, we can understand that AKI is a subset of acute kidney disease (Figure 1).

▪ Chronic kidney disease (CKD): glomerular filtration rate (GFR) < 60 ml/min/1.73m2 persisting for > 3 months. Within this, episodes of acute renal dysfunction may occur, which we must act on.

Etiology and pathophysiology of kidney disease

Main etiologies:

We can define three main groups as causes of AKI in cirrhotic patients, which may coexist in the same patient[3],[10],[11]:

Prerenal: caused by renal hypoperfusion, it is the most common cause of this dysfunction in cirrhotic patients. Noteworthy etiologies in this group include hypovolemia (27-50% of cases) and hepatorenal syndrome (15-20%.

Intrinsic: resulting from direct damage to the renal parenchyma. The main etiological factor in this group is acute tubular necrosis (ATN) (14-30%), which can occur in cases of hypovolemic or septic shock or also due to the direct action of nephrotoxic drugs or iodinated contrast media. Other processes to consider are those that lead to acute interstitial nephritis (AIN), such as: biliary acid nephropathy, glomerulonephritis (IgA-mediated in alcoholic patients or membranous/membranoproliferative in cirrhotic patients with HBV/HCV).

Postrenal: this includes processes that cause obstruction of the urinary tract (lithiasis, tumors, etc.). It usually occurs in less than 1% of cases.

Hepatorenal syndrome:

Hepatorenal syndrome (HRS) is a phenotype of prerenal AKI that occurs in patients with ACLD and ascites, characterized by impaired renal function secondary to reduced renal perfusion due to hemodynamic alterations in arterial circulation and hyperactivity of endogenous vasoactive systems. Systemic inflammation contributes to the neurohumoral and vasodilator disorders that give rise to this type of renal dysfunction, which is persistent with volume expansion therapies and may be reversible with vasoconstrictor therapy[12]-[14]. It is therefore essential that in all patients with ACLD and ascites who present with AKI, we carry out an adequate and rapid evaluation and differential etiological diagnosis in order to ensure timely etiological recognition and management, always taking into account the possibility of coexisting causes of AKI[3][5],[12]. Currently, following the latest consensus reached, we can discard the old concepts of type 1 and type 2 HRS, which have been replaced by the terms HRS-AKI, HRS-AKD, and HRS-CKD, whose diagnostic criteria are outlined in the following table (Table 2)[5]:

Table 2

Criterios diagnósticos de síndrome hepatorrenal según consenso ADQI-ICA de 2024.

The following aspects of these new diagnostic criteria should be highlighted in comparison with those previously established[5],[15]-[17]:

Assessing response to volume expansion with albumin over 48 hours: this criterion is excluded because in euvolemic patients or those with intravascular fluid overload, 48 hours of albumin infusion can be harmful, promoting fluid accumulation and delaying diagnosis and initiation of vasoconstrictor therapy.

No improvement in renal function despite adequate volume expansion for 24 hours: it is recommended to assess the patient's volemia status for 24 hours with adequate intravenous fluid infusion, either balanced crystalloids (Ringer's Lactate or PlasmaLyte) or 20% albumin solution at a rate of 1 g/kg of weight (maximum 100 g per day), depending on the patient's clinical condition. If there is no improvement in sCr within 24 hours, a diagnosis of HRS-AKI should be considered.

Coexistence of other etiologies: the presence of underlying kidney disease does not currently exclude a superimposed diagnosis of HRS, which is why HRS can coexist with other causes of AKI, which we must always take into account in the diagnosis. Therefore, in all patients with AKI or suspected HRS, we must look for an alternative explanation such as septic shock requiring vasopressors, acute tubular necrosis, renal obstruction, etc.

We will therefore distinguish between AKI, AKD, and CKD types of HRS depending on the timing and duration of renal dysfunction. HRS lasting less than 90 days would be classified as AKI-HRS, while HRS lasting more than 90 days would be classified as CKD-HRS[5].

Example 1: A patient with baseline HRS-AKD who develops acute renal dysfunction or AKI should be classified at this new stage as HRS-AKI.

Example 2: A patient with pre-existing ACLD and CKD due to diabetic nephropathy who develops acute renal dysfunction with HRS criteria will be classified as HRS-AKI in CKD.

Pathophysiology

Patients with ACLD, and particularly those with ascites, are more susceptible to AKI due to hemodynamic alterations resulting from portal hypertension. The degree of hepatic, renal, and circulatory dysfunction, together with precipitating events, can give rise to a variety of clinical phenotypes of AKI[3],[5],[18],[19].

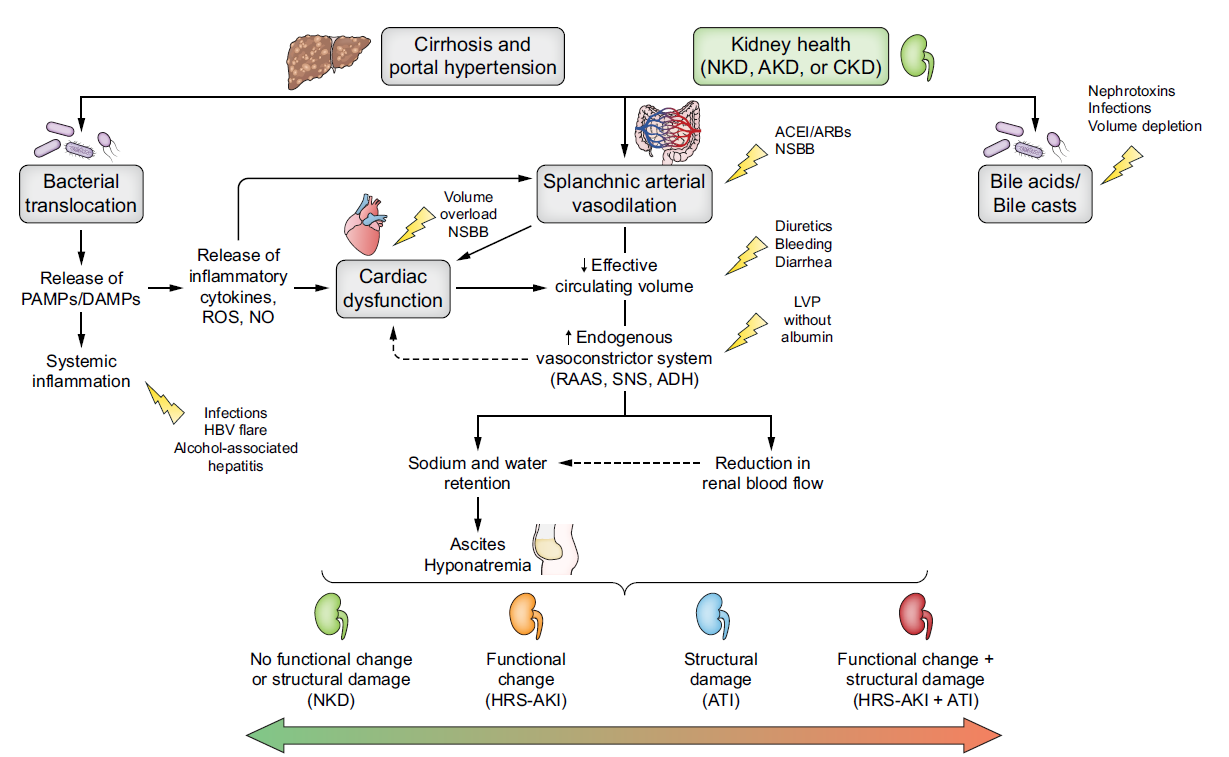

The pathophysiology of this dysfunction is based on four axes (Figura 2), with portal hypertension being the basis of everything:

Figure 2

Pathophysiology of renal dysfunction in patients with advanced chronic liver disease and triggering factors. Extracted from: Nadim MK, Kellum JA, Fomi L, et al. Acute kidney injury in patients with cirrhosis: Acute Disease Quality Initiative (ADQI) and International Club of Ascites (ICA) joint multidisciplinary consensus meeting. J Hepatol. 2024; 81: 163-83.

Systemic circulatory dysfunction:

The initial mechanism in the pathogenesis of portal hypertension is increased intrahepatic resistance secondary to distortion of the hepatic architecture and/or increased vascular tone of the splanchnic axis. This increase in resistance, together with the systemic proinflammatory state resulting from liver disease and reduced hepatic elimination of endogenous substances, promotes increased production of endogenous vasodilator factors such as nitric oxide, carbon monoxide, and endocannabinoids in the splanchnic circulation. These vasodilator mediators promote splanchnic arterial vasodilation, causing a redistribution of systemic blood flow to this splanchnic vascular territory, thus decreasing arterial perfusion of other vascular territories (effective arterial hypovolemia). As a result of all this, mean arterial pressure (MAP) decreases, promoting the activation of compensatory mechanisms, mainly the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS), the sympathetic nervous system (SNS), and arginine vasopressin. These systems are progressively activated in order to maintain blood pressure, effective arterial blood volume, and renal perfusion, leading to a state of hyperdynamic circulation.

As liver disease progresses, portal hypertension and splanchnic vasodilation increase, leading to hyperactivation of compensatory systems to such an extent that there is an increase in water and solute-free sodium retention, causing effective arterial hypovolemia that results in the development of ascites, edema, or hypervolemic hyponatremia, among other conditions[3],[20],[21].

Renal vasoconstriction

At the renal level, as a result of this state of hypovolemia and progressive activation of the RAAS and SNS, vasoconstriction of the renal arteries and a reduction in the glomerular filtration rate occur.

Under physiological conditions, renal blood flow remains constant despite variations in blood pressure, a phenomenon known as autoregulation of renal circulation. In advanced stages of liver disease, this balance is lost, leading to a disproportionate increase in renal vascular resistance, thus causing a decrease in renal perfusion and glomerular filtration rate[22]-[24].

Cardiac dysfunction

In the early stages of ACLD with associated portal hypertension, a hyperdynamic circulatory state is favored in order to maintain MAP within the normal range and maintain tissue perfusion. This hyperdynamic state is characterized by increased cardiac output, heart rate, and plasma volume. However, in the advanced stages of the disease, after a long period of maintaining this hyperdynamic state, both systolic and diastolic cardiac dysfunction (called "cirrhotic cardiomyopathy") occurs, contributing to renal hypoperfusion[25],[26].

Proinflammatory state

Systemic inflammation is a common condition in patients with decompensated ACLD, presenting elevated levels of proinflammatory cytokines such as interleukin 6, tumor necrosis factor α, and C-reactive protein, among others. This proinflammatory state in cirrhotic patients is associated with increased intestinal permeability, thus promoting bacterial translocation from the intestine to the portal circulation. The passage of bacteria into the bloodstream activates antigen-presenting cells (macrophages, monocytes, and dendritic cells) through pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), endotoxins, and bacterial DNA. In addition to these factors associated with bacterial translocation, cirrhotic patients present a proinflammatory state secondary to liver cell damage induced by the various noxious agents that cause the disease, which trigger the release of damage-associated molecules (DAMPs) such as uric acid, S100 proteins, etc., which also promote the activation of the innate immune system. Therefore, the activation of innate immune cells promotes the release of proinflammatory and vasodilatory cytokines, leading to increased systemic vasodilation and worsening of the hyperdynamic circulatory state in these patients[27]-[32].

Precipitating factors

This renal failure can occur spontaneously secondary to disease progression and exhaustion of the compensatory system, or it can be associated with a series of precipitating factors[3],[5]:

Potentiation of the proinflammatory state: infectious processes, mainly spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (the most frequent trigger of AKI); persistence of active hepatic noxious agents (alcohol, HBV, HCV, etc.).

Systemic volume depletion: gastrointestinal bleeding, large-volume paracentesis, excessive diuresis (excessive use of diuretics), diarrhea/dehydration, etc.

Circulatory dysfunction: refractory ascites, drug-induced vasodilation (ACE inhibitors, ARBs, beta-blockers, etc.), impaired renal circulation autoregulation (NSAIDs) Renal damage: nephrotoxic substances (NSAIDs, aminoglycosides, iodinated contrast media, etc.).

Diagnosis and evaluation of renal function

The diagnostic evaluation of patients with ACLD and AKI should be based on determining intravascular volume status, evaluating renal function, and thoroughly screening for possible triggering factors and phenotyping AKI[5].

Intravascular volume assessment

Today, this remains a complex clinical challenge, as most of the tools available for hemodynamic monitoring have not been validated in patients with ACLD.

Point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) is proposed as a basic tool for assessing the patient's intravascular volume status at the bedside, but it has certain limitations, such as interobserver variability and difficulty in use in patients with significant ascites. Other options have been proposed, such as urinary sediment analysis or even renal biopsy, but all of these have significant limitations, which means that intravascular volume assessment remains a challenge to be resolved in the coming years[3],[5],[15],[33],[34].

Assessment of renal function

Scr is the established marker for determining the diagnostic criteria and stages of renal failure in cirrhotic patients. However, it is a marker with certain limitations, such as being influenced by muscle mass, changes in distribution volume, or even possible interference with bilirubin. These limitations are common in cirrhotic patients and can delay the diagnosis of renal failure[34],[35].

The latest ADQI-ICA consensus proposes the use of the CKD-EPI equation without the racial variable and using cystatin C (CysC) instead of sCr to assess the estimated glomerular filtration rate in cirrhotic patients, as this allows for a better estimation of renal function with less associated bias in these patients[5],[36],[37].

Trigger factors and phenotyping of AKI

In addition to studying renal function, recent consensus statements on renal failure in cirrhotic patients recommend early detection of possible triggers of renal failure[38]. For this investigation, we must rely on a correct patient history and use various biochemical markers, including those related to kidney damage, in order to facilitate the detection of AKI, identify its origin, and thus be able to direct the therapeutic strategy more accurately[5].

The study of albumin and proteins in urine, together with urinary neutrophil gelatinase lipocalin (uNGAL), are proposed as markers of structural kidney damage. NGAL is a widely studied and promising biomarker, which is not easily found in our hospitals, mainly due to its high cost. It will facilitate the differential diagnosis between acute tubular necrosis and the prerenal origin of renal dysfunction. NGAL values ≥ 220 pg/d of creatinine point to a structural origin of AKI[39]-[41].

Prevention

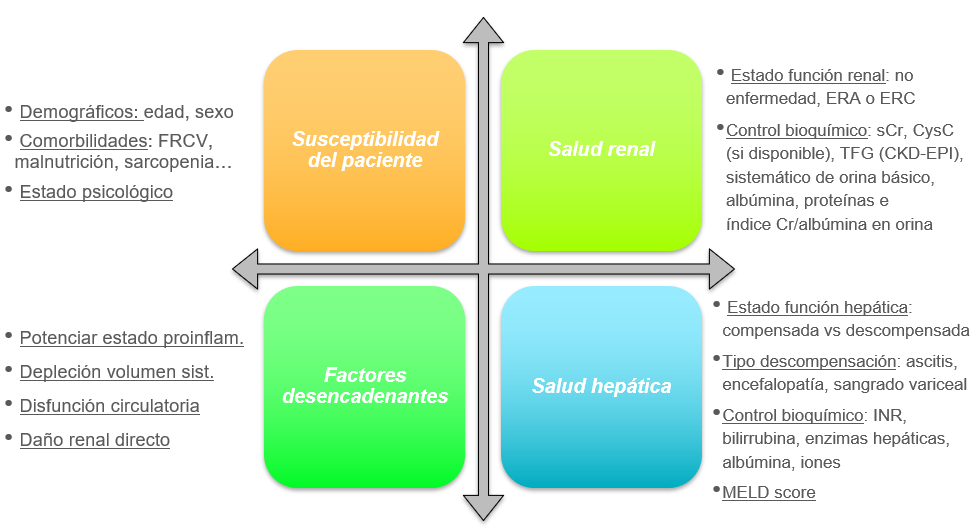

The development of renal dysfunction in cirrhotic patients is a common and serious complication, so it is essential that all patients with advanced chronic liver disease undergo a complete assessment of their renal and hepatic health (Figure 3) based on a comprehensive medical history that evaluates the patient's susceptibility to developing AKI based on their history; knowledge of drugs and events that trigger such dysfunction, and awareness of the patient's renal and hepatic function[5],[42][43].

Based on all of the above, and mainly on the various main triggering events, the ADQI-ICA proposes the following strategies to prevent the development of AKI in cirrhotic patients (Table)[5]:

Figure 3

Comprehensive assessment of renal and hepatic health in cirrhotic patients. Adapted from: Nadim MK, Kellum JA, Fomi L, et al. Acute kidney injury in patients with cirrhosis: Acute Disease Quality Initiative (ADQI) and International Club of Ascites (ICA) joint multidisciplinary consensus meeting. J Hepatol. 2024; 81: 163-83.

Tabla 3

Preventive strategies to prevent AKI in patients with cirrhosis according to possible triggering factors. *Alfapump®, abdominal cavity-to-bladder pump for the treatment of ascites. Adapted from: Nadim MK, Kellum JA, Fomi L, et al. Acute kidney injury in patients with cirrhosis: Acute Disease Quality Initiative (ADQI) and International Club of Ascites (ICA) joint multidisciplinary consensus meeting. J Hepatol. 2024; 81: 163-83.

General therapeutic strategy for acute renal failure

In general, in all patients with hepatic ACLD and development of AKI, a therapeutic strategy should be implemented based on knowledge of the patient's hepatic and renal health and the AKI phenotype encountered[5],[15].

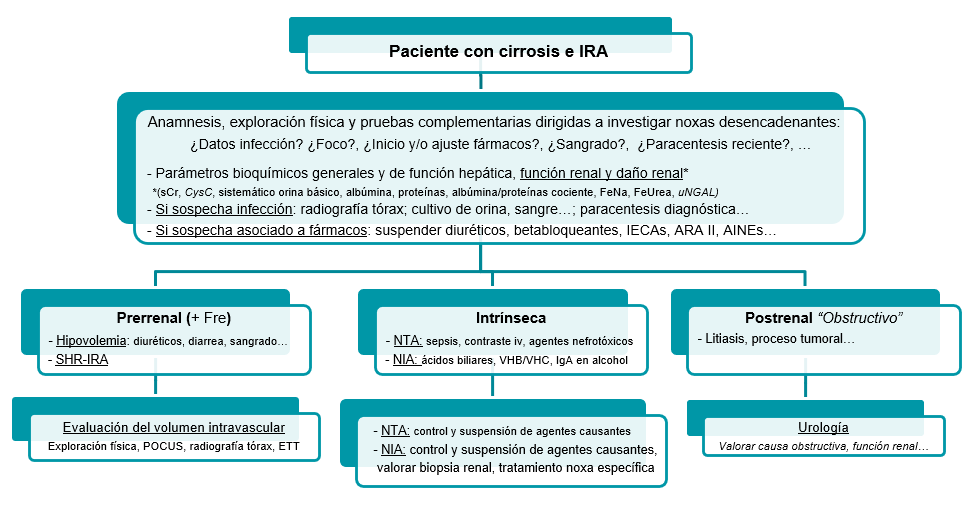

Initially, we will carry out an assessment of the patient's overall health, focusing mainly on the liver and kidneys, and proceed to investigate any triggering events and their subsequent correction and/or suspension if necessary (Figure 4)[5],[15],[44].

Figure 4

Initial management of patients withadvanced chronic liver disease and acute renal dysfunction.

Once this step has been completed and the probable phenotyping of the causal origin of the dysfunction has been carried out, we will direct therapy based on the suspected AKI phenotype, maintaining optimal hemodynamic and volumetric status in the patient at all times[3],[5],[15]:

Intrinsic: any causative nephrotoxic agent should be discontinued, and if the patient does not show proper clinical progress, a renal biopsy should be considered.

In specific cases of specific glomerular pathology, the use of specific treatment necessary for the condition should be considered, in consultation with the appropriate specialists.

En los casos concretos de patología glomerular específica, se debe valorar el empleo de tratamiento específico necesario para la misma, en consonancia con los especialistas oportunos.

Postrenal: the therapy to be followed will be assessed in consultation with the urology department of our centers, based primarily on the obstructive cause and renal function.

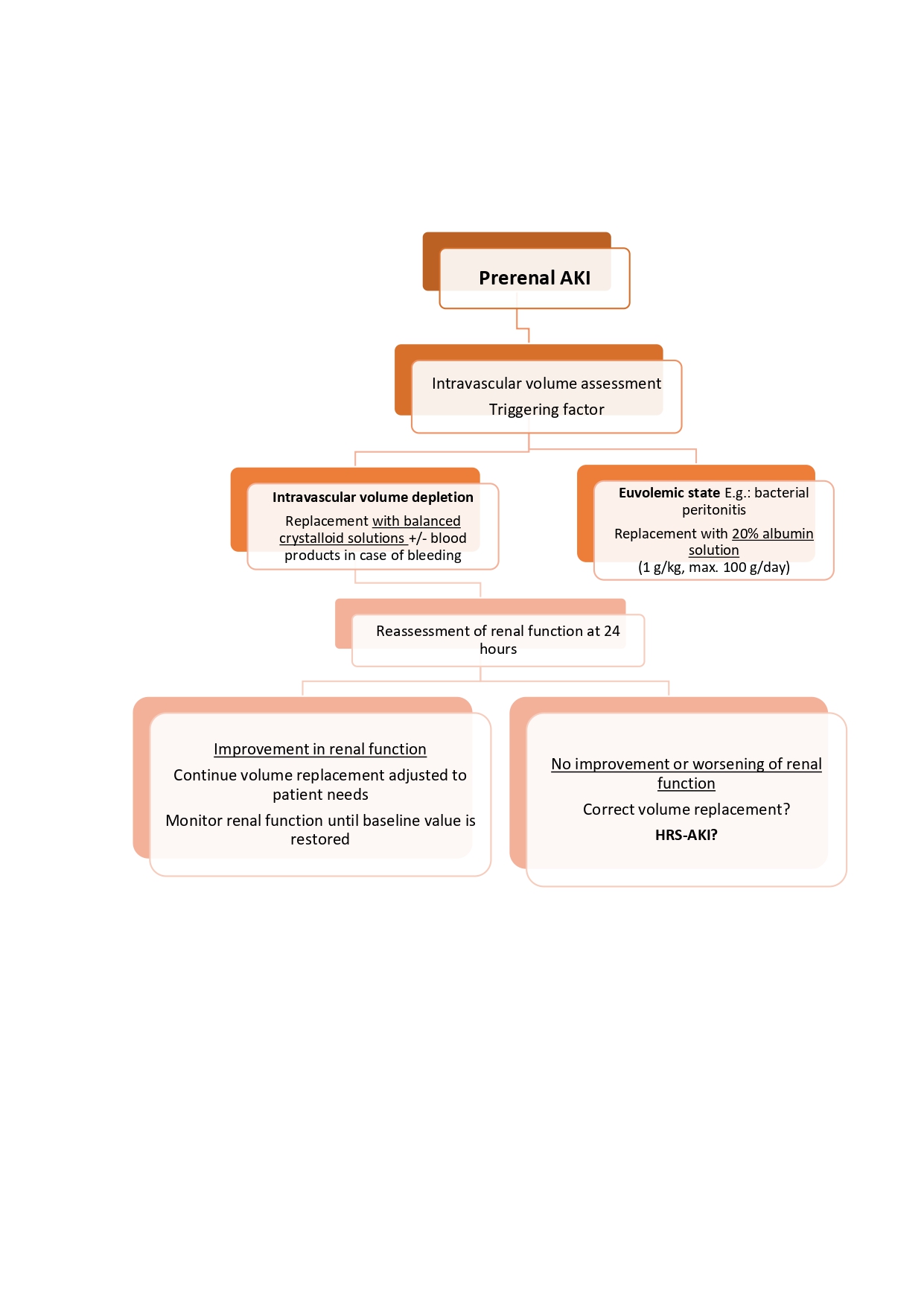

Prerenal: an initial overall assessment of the patient's volume status is recommended in order to carry out a correct and safe restoration of systemic volume, thus avoiding iatrogenic volume overload (Figura 5).

The latest ADQI-ICA consensus recommends the use of balanced crystalloid solutions[45],[46] as first-line therapy for volume replacement in patients with renal dysfunction who require volume resuscitation, unless there is a specific indication for the use of other fluids. Even so, we recommend that the choice of fluids should be individualized, depending on the specific condition of the patient[3].[5],[15],[47]:

Intravascular volume depletion: replacement with balanced crystalloid solutions, combined with replacement with blood products in cases of gastrointestinal bleeding.

Euvolemic state (e.g., bacterial peritonitis): replacement with 20% albumin solution at a dose of 1 g/kg of weight (maximum of 100 g per day).

Twenty-four hours after starting effective volume replacement, sCr monitoring is recommended:

If renal function improves: continue with volume replacement adjusted to the patient's needs and monitor renal function until values close to baseline are achieved.

No improvement or worsening of renal function: ensure effective volume replacement, and if so, assess HRS-AKI criteria and consider initiating early measures for this AKI phenotype.

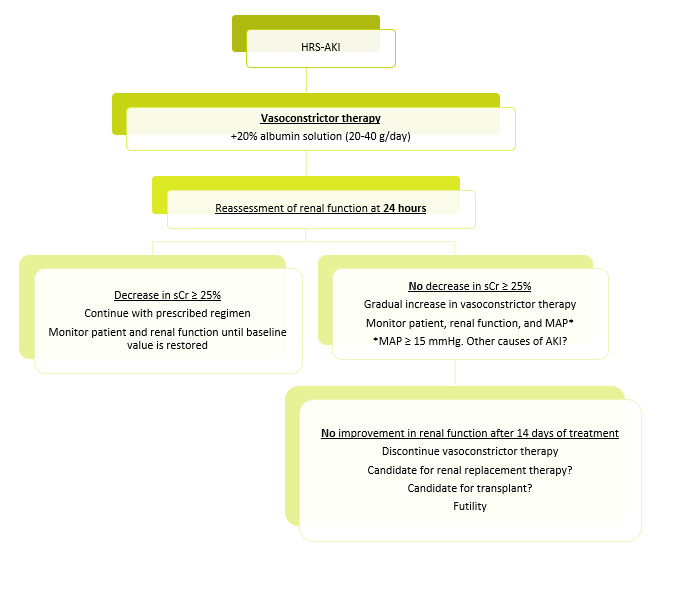

Therapeutic strategy for HRS-AKI

Once a diagnosis of suspected HRS-AKI has been established, vasoconstrictor therapy (terlipressin as the first-line agent) (Table 4) should be initiated as soon as possible in combination with 20% albumin (20-40 g per day)[5],[12],[49].

Tabla 4

Terapias vasoconstrictoras disponibles para el tratamiento del SHR-IRA: vías de administración, dosis, consejos para su uso y criterios de suspensión de esta.

Once this therapy has been initiated, close monitoring of the patient and control of systemic volume are recommended to avoid adverse reactions[49]-[52]:

Ischemic events: (cardiac, peripheral, and/or mesenteric), mainly associated with vasoconstrictor therapy and usually controlled by the use of infusion versus boluses of these drugs, or in certain cases requiring a reduction or even suspension of these.

Volume overload: the combination of vasoconstrictor drugs with intravenous albumin infusion promotes an increase in systemic volume. For this reason, close monitoring is recommended, and in the event of signs and/or symptoms suggestive of fluid overload, temporary suspension of albumin, reduction of vasoconstrictor drug doses, and consideration of co-administration of diuretic drugs is advised.

Twenty-four hours after starting this therapy, monitoring of sCr is recommended.

Decrease in sCr ≥ 25% from the previous level: continue with the treatment initiated and monitor the patient and renal function until values close to baseline are achieved.

NO decrease in sCr ≥ 25% from the previous level: a gradual increase in the dose of vasoconstrictor drugs and continuous monitoring of the patient and renal function are recommended until the target is achieved.

In this situation, it is also advisable to monitor mean arterial pressure (MAP), as various studies have shown an improvement in renal function when associated with an increase in MAP ≥ 15 mmHg in patients treated with vasoconstrictor therapy. Therefore, if this increase in MAP occurs without an improvement in sCr, alternative causes of AKI should be reevaluated[53],[54].

Discontinuation of vasoconstrictor therapy should be considered if renal function does not improve after a maximum of 14 days of treatment or after 48 hours at maximum tolerated doses, if serious adverse events develop, or if another alternative therapy is indicated[5],[12].

Other therapeutic options

Renal replacement therapy (RRT)

Early initiation of RRT should be considered in cirrhotic patients who develop AKI and experience adverse events that are refractory to targeted medical treatment, such as hyperkalemia, acidosis, or intravascular volume overload that does not respond to diuretic treatment or cannot be corrected with diuretics without causing serious adverse events, such as electrolyte disturbances or hepatic encephalopathy[55]-[57].

It is also considered as a bridge therapy option to transplantation in patients with HRS-AKI who do not respond to vasoconstrictor therapy or who experience severe adverse events to it, requiring its discontinuation. If the patient is not a candidate for liver transplantation, RRT is considered futile therapy, and its use should be assessed on an individual basis[12].

Liver transplantation (LT)

Episodes of AKI are associated with a high risk of short-term mortality in cirrhotic patients, especially those with a high baseline MELD score. For this reason, accelerated evaluation for LT is recommended in patients with decompensated ACLD after overcoming an episode of AKI.

In patients who develop HRS-AKI, liver transplantation is the treatment of choice and should be considered regardless of the response to vasoconstrictor therapy. Simultaneous kidney and liver transplantation is a potential therapeutic option in cases of patients who are candidates for liver transplantation and have prolonged renal dysfunction, as recovery of renal function is less likely in these patients than in those with a shorter duration of renal dysfunction. In 2017, the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network established the following criteria for simultaneous liver and kidney transplantation: prolonged duration of acute renal dysfunction (≥ 6 weeks), need for renal replacement therapy, and presence of CKD[58]-[60].

Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS)

There is currently insufficient evidence to support the use of TIPS for the treatment of AKI[3],[5],[12]. Several clinical trials are underway to provide evidence of the benefits of this therapy in renal dysfunction in cirrhotic patients[61]-[64]. Of particular note is the result of a meta-analysis suggesting that TIPS implantation leads to a significant improvement in renal function in cirrhotic patients with HRS-AKI, as it improves renal function by redistributing systemic blood volume and thus reducing portal pressure[65].

Outpatient follow-up

The period following hospital discharge after acute renal failure in cirrhotic patients is a critical time when dynamic changes in liver and kidney function can determine the patient's prognosis. In fact, after this episode of hospitalization, these patients have a higher associated risk of recurrent episodes of AKI, progression to CKD, dependence on renal replacement therapy, and morbidity and mortality[66]-[70].

It is recommended that, at least one month after hospital discharge, the renal and hepatic health of cirrhotic patients be reassessed to confirm the degree of recovery or progression of renal disease. In this assessment, it is advisable to evaluate the patient's liver function using standard prognostic scores and kidney function, including determination of sCr, serum CysC levels (which provide more reliable values of kidney function status) if available, and detection of albumin and proteins in urine. Several studies have shown that these latter values help us identify patients who are at greater risk of progression to CKD.

This assessment should also be based on continuing preventive measures to care for the patient's renal and hepatic function, based on the key elements mentioned above (Figure 3); a fundamental pillar of these assessments being therapeutic reconciliation with the patient, especially with diuretic and beta-blocker drugs, in order to establish a balance between renal and hepatic function[71]-[74].

In cases of persistent renal dysfunction at 90 days, these patients should be formally evaluated for possible development or progression to CKD; These patients are eligible for a multidisciplinary approach focused on their life prognosis and hepatorenal health status, to determine whether they are candidates for transplantation or, on the contrary, require comprehensive management in which palliative care plays a fundamental role in the follow-up and planning of patient care[5],[75],[76].

Conclusions

- Acute kidney injury (AKI) is a common complication in patients with advanced chronic liver disease (ACLD), with a variable prevalence of up to 53% in patients with decompensated ACLD, and a marker of high morbidity and mortality and progression to chronic kidney disease after transplantation.

- The diagnostic criteria for AKI have evolved, incorporating decreased urine output as a complementary criterion, reflecting an effort to advance the detection and management of AKI in the cirrhotic population.

- The etiology of AKI in cirrhotic patients is multifactorial, with causes including prerenal, intrinsic, and postrenal factors, with renal hypoperfusion and hepatorenal syndrome (HRS) being particularly prevalent.

- HRS has been redefined and more appropriately classified into HRS-AKI, HRS-AKD, and HRS-CKD, based on a detailed assessment that includes the absence of response to adequate volume expansion over 24 hours, preferably with balanced crystalloid solutions, and the absence of strong evidence for an alternative explanation as the primary cause of renal failure. The pathophysiology of AKI in the context of ACLD is complex and involves systemic circulatory dysfunction, renal vasoconstriction, cardiac dysfunction, and proinflammatory states, all of which are influenced by portal hypertension and its hemodynamic consequences

- The prevention of AKI should be based on a comprehensive assessment of renal and hepatic health, as well as on knowledge and management of the factors that trigger renal dysfunction

- The therapeutic strategy for managing AKI in cirrhotic patients should be personalized and targeted according to the suspected etiology, with the correction and/or suspension of the triggering noxa, the assessment and replacement of volume, and the early evaluation of alternative therapies: vasoconstrictor therapy if HRS-AKI develops, renal replacement therapy, and/or simultaneous liver and/or kidney transplantation.

Outpatient follow-up is crucial for reassessing renal and hepatic health after an episode of AKI, with particular emphasis on preventing progression to chronic kidney disease, adjusting diuretic and beta-blocker therapy, and planning care in the event of persistent renal dysfunction

Descargar número completo

Descargar número completo Download full issue

Download full issue