CORRESPONDENCIA

Alejandro Garcia Martinez

Punta de Europa University Hospital. Algecira, Cadiz.

11207 Algeciras, Cádiz

CITA ESTE TRABAJO

García Martínez A, Mateos Millán D, Morales Prado A. Gastrointestinal bleeding secondary to duodenal vascular anomaly due to median arcuate ligament syndrome. RAPD 2024;47(6):212-214. DOI: 10.37352/2024476.2

Introduction

The celiac trunk is an artery that arises in close proximity to the diaphragm and has an important anatomical and pathophysiological relationship with this structure. On the other hand, the median arcuate ligament (MAL) is a fibrous arch at the base of the diaphragm that connects the right and left diaphragmatic crura at the aortic hiatus[1],[2]. Certain anatomical variants of this ligament can sometimes cause direct compression of the celiac trunk[1],[3]. However, if this compression is significant, it can manifest as median arcuate ligament syndrome (MALS) and its clinical features are derived from foregut ischaemia, i.e. postprandial epigastralgia, weight loss and sitophobia (fear of eating)[1],[4]. Other less frequent but more serious manifestations are related to the development of aneurysms, especially in the pancreaticoduodenal arteries, either in the form of gastrointestinal or retroperitoneal haemorrhage. These constitute less than 2% of visceral arterial aneurysms and are usually due to atherosclerosis, pancreatitis, trauma and fungal or bacterial infections. There are also case reports describing an association between MALS and aneurysms of the pancreaticoduodenal artery[4].

Clinical case

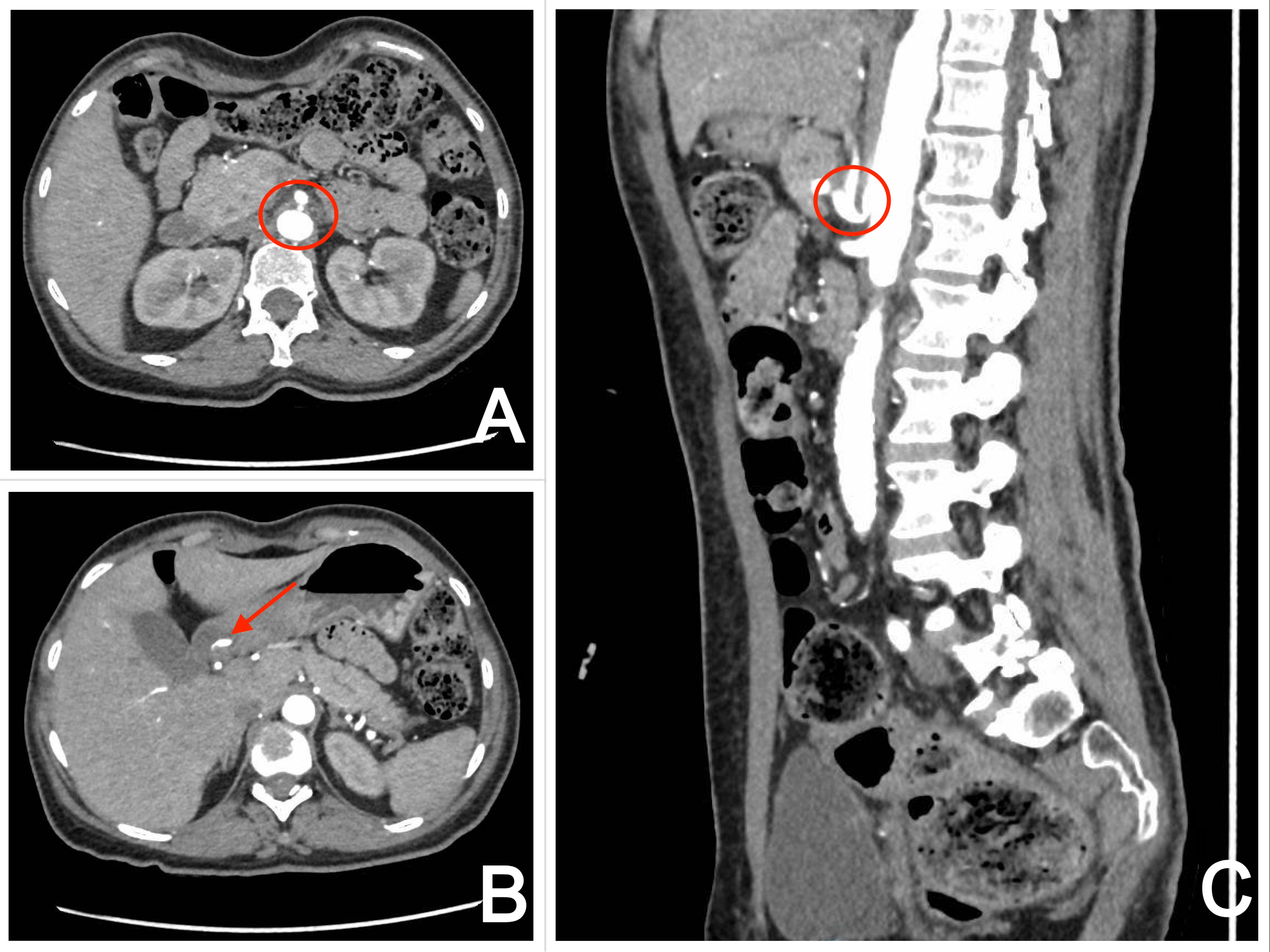

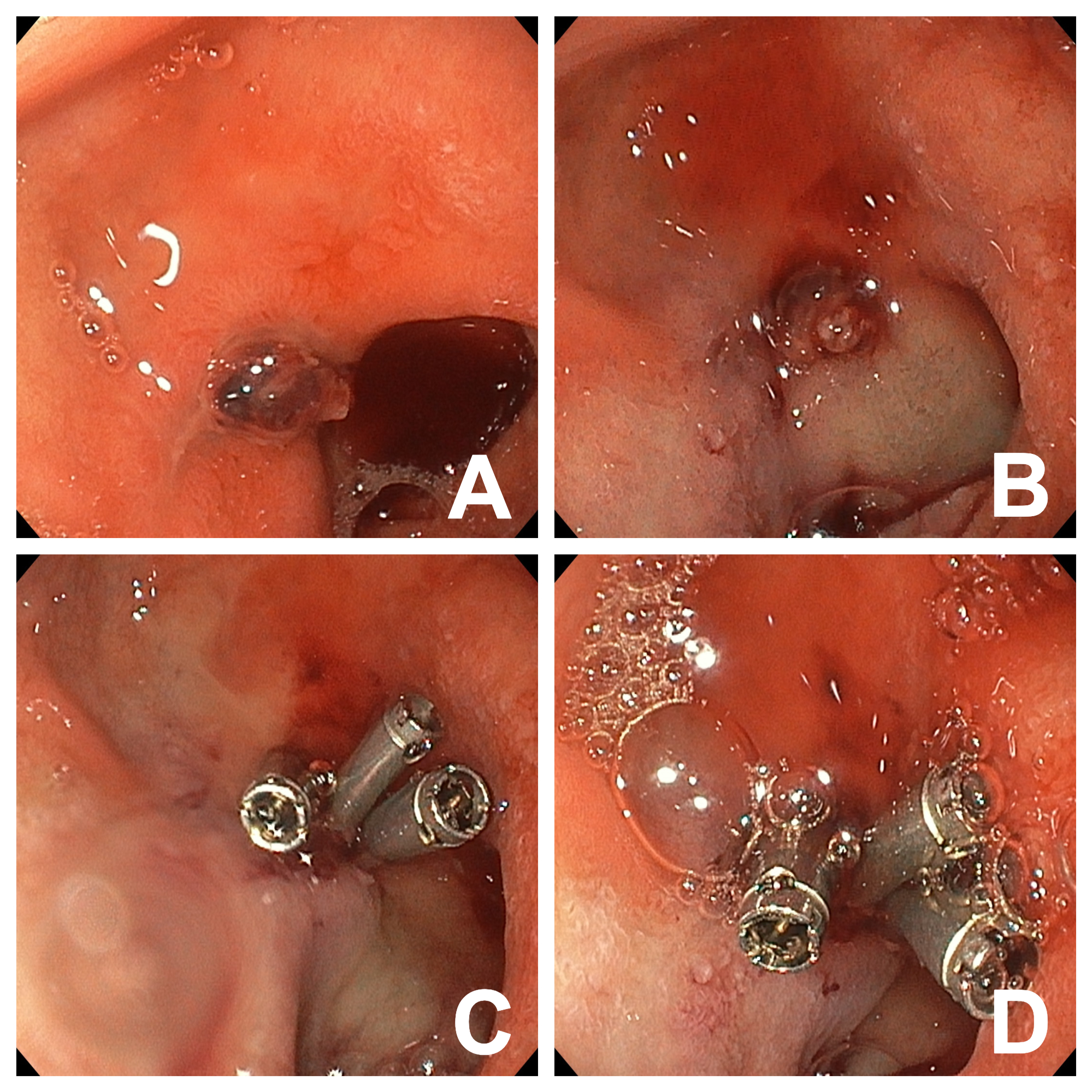

A 52-year-old woman with a personal history of CADASIL syndrome (cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy) under follow-up by Neurology and dependent for basic activities of daily living was admitted for asthenia, dizziness and anaemia (Hb 5.1 g/dl), with no evidence of bleeding. A thoracoabdominal CT scan was performed with a finding of compression of the celiac trunk by the median arcuate ligament. Therefore, a further study was carried out by CT angiography, confirming significant non-atherosclerotic stenosis at the exit of the celiac trunk due to compression by the median arcuate ligament of the diaphragm. In addition, the celiac trunk was visualised in the form of a ‘hook’, with post-stenotic dilatation of the pancreaticoduodenal arcades and an aneurysm of a submucosal pyloroduodenal artery (Figure 1). The day after the CT angiography, the patient began to develop melena and haemodynamic instability, for which reason oral endoscopy was performed and a large clot was found in the anterior aspect of the duodenal bulb, which was removed and a visible vessel was visualised. It was treated with diluted perilesional adrenaline and three haemostatic clips, with good endoscopic results (Figure 2). The patient's subsequent clinical evolution was favourable, with progressive recovery of haemoglobin levels. However, given the radiological findings, the possibility of embolisation and surgery was considered with interventional radiology, but both approaches were rejected given the good evolution of the patient and considering her fragility. Subsequently, CT angiography was repeated without observing the submucosal aneurysmal arterial vascular structure in the duodenal bulb due to probable resolution after endoscopic treatment. Finally, the patient was discharged from hospitalisation and presented no clinical incidents in her subsequent follow-up.

Discussion

This case draws attention to the complexities of MALS and its association with complications such as aneurysms, particularly of the pancreaticoduodenal artery[4]. Approximately 7-15% of these aneurysms are associated with haemorrhage, particularly in the retroperitoneal space. When an aneurysm ruptures, mortality rates can be as high as 50% [4],[5].

In MALS, blood flow to the splanchnic organs is redirected to the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) and the pancreaticoduodenal arcades due to the lowering of blood flow in the celiac trunk. Although there is no proven causal mechanism for this relationship, it is thought that these pancreaticoduodenal arcades and other more distal branches would not support this increased flow, leading to increased shear stress on the arterial wall, formation of pseudoaneurysms, growth of these and eventually spontaneous rupture[2],[4]. Unlike other types of aneurysms, the risk of rupture is not directly proportional to the diameter of the aneurysm itsel[3],[5],[6].

The diagnosis of MALS is made by a combination of symptoms and compatible imaging findings. It is sometimes difficult and is made by chance or after the occurrence of a complication. The gold standard for the diagnosis of MALS is CT angiography where the characteristic ‘’hook‘’ shape of the celiac trunk is identified during expiration. However, Doppler ultrasound is a non-invasive method and is more widely available, which would be a valid alternative in certain cases[2],[4].

Treatment of MALS consists primarily of surgical release of the ligament, thus improving blood flow. Endovascular techniques are available as alternatives, but they have higher rates of therapeutic failure[4]. However, there are currently no consensus or treatment protocols for the management of this type of aneurysm, thus posing a major therapeutic challenge. Early treatment of these aneurysms is critical to prevent serious complications, as in our case, due to the high risk of spontaneous rupture. Some authors propose embolisation of the aneurysm as the sole treatment while others suggest releasing the stenosis from the celiac trunk. If the stenosis-relieving approach is chosen, there is a better chance of avoiding aneurysm recurrence. In contrast, in asymptomatic individuals with incidental finding of MALS there seems to be no indication for treatment[4],[7].

In conclusion, MALS is an underestimated clinical entity and with this clinical case we want to increase the index of suspicion in the medical population, as it can lead to serious complications.

Descargar número completo

Descargar número completo Download full issue

Download full issue