CORRESPONDENCIA

José Antonio Aguirre Sánchez-Cambronero

Mancha Center General Hospital

13600 Ciudad Real

CITA ESTE TRABAJO

Aguirre-Sánchez Cambronero JA, Rodríguez Fernández S, Pérez Villafáñez A, Arias Ortega M, Legaz Huidobro ML, González Carro P. Splenic infarction without thrombosis secondary to severe acute pancreatitis. RAPD 2024;47(6):195-197. DOI: 10.37352/2024475.6

Introduction

Acute pancreatitis is a disease with a high and increasing incidence in our environment and is a frequent cause of hospitalisations[1]. Vascular complications are an infrequent complication of severe pancreatitis[1], including splenic infarction, which is increasingly being described in association with inflammatory processes of the pancreas, justified by the close relationship between the pancreas and the splenic hilum[2].

Clinical case

A 71-year-old woman was admitted for acute pancreatitis with a torpid evolution throughout the first admission. Two weeks later, she presented clinical and analytical worsening due to acute cholecystitis, which was detected in imaging tests and treated with empirical antibiotic therapy. One month after admission, he presented a new clinical and analytical worsening, and an echoendoscopy was performed, visualising a small collection of 4cm in the pancreatic body with a permeable splenic axis and another collection suggestive of an infected encapsulated necrotic collection measuring 6x6x8cm adjacent to the compressing gastric body, and transmural drainage was performed using a Hot-Axios luminal apposition metal prosthesis, draining abundant pus. On successive days, endoscopic necrosectomy was performed through the prosthesis, which was finally removed and a 7Frx10cm pig-tail plastic prosthesis was placed, with radiological improvement prior to discharge. In addition, enzyme replacement treatment with Kreon 50000 was started after each main meal.

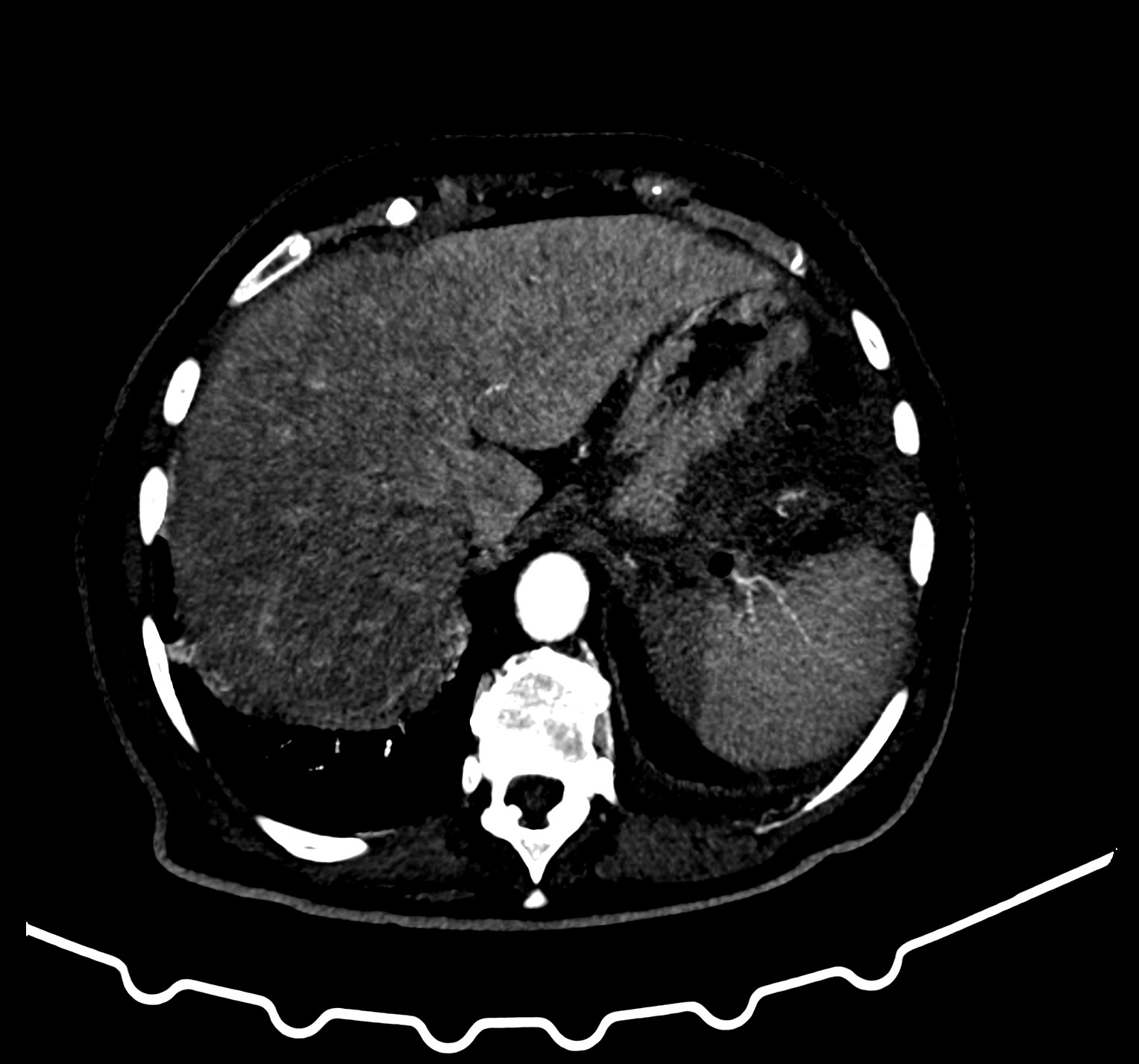

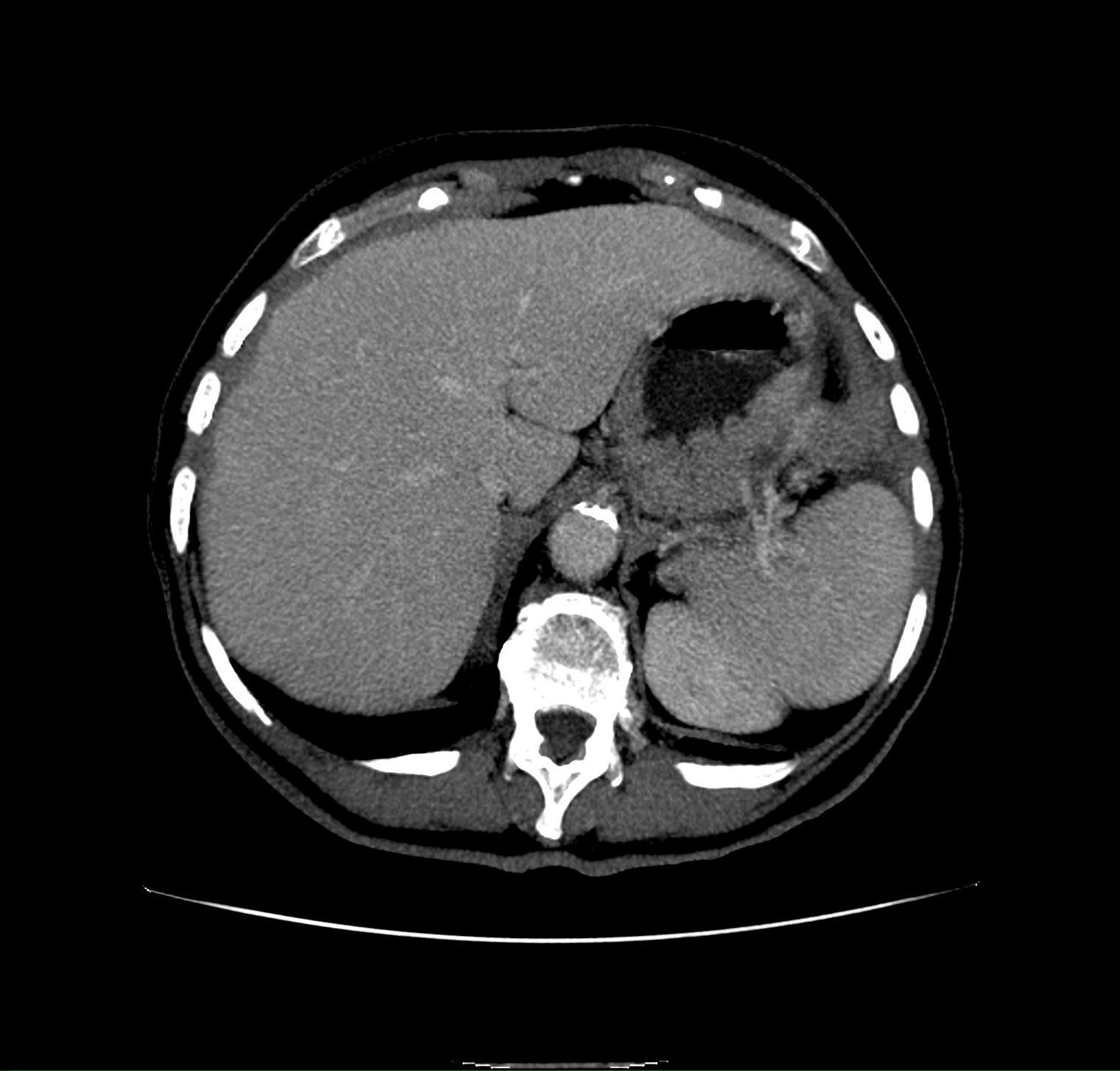

One and a half months later, the patient came to the emergency department complaining of severe abdominal pain in the left hypochondrium-flank without fever. Laboratory tests showed elevated acute phase reactants, thrombocytosis, mild coagulopathy and a normal pancreatic profile. An abdominal CT scan was requested, showing radiological worsening with a greater inflammatory component and peripancreatic fluid, very thinned splenic vein with permeable splenic artery and signs compatible with splenic infarction without identifying thrombosis (Figure 1) with associated thrombocytosis (700,000 platelets/mm3). It was decided to anticoagulate the patient with enoxaparin at prophylactic doses due to splenic vascular stenosis. After discharge and review in consultation, resolution of the thrombocytosis (410,000 platelets/mm3) and stenosis was observed due to a decrease in the pancreatic inflammatory component, homogenisation of the spleen and disappearance of the splenic necrotic zone (Figure 2) with no new collections and a decrease in inflammatory changes in the control CT scan; anticoagulation was therefore withdrawn.

Discussion

Splenic infarction is a complication increasingly described in association with inflammatory processes of the pancreas, the incidence of which is increasing. The most frequent symptom is left hypochondrium pain, which may be accompanied by fever, chills, nausea and vomiting, pleuritic pain and left shoulder pain (Kher's sign)[2] as described in our patient.

In splenic infarction associated with arterial and/or venous thrombosis, the treatment of choice is anticoagulation without specifying the drug used[3]. A recent retrospective cohort study has compared the benefits of initiating anticoagulation with both heparin followed by vitamin K antagonists and the use of direct-acting oral anticoagulants, establishing that there is an improvement in survival without increasing the risk of bleeding[4]. Thrombolysis and/or thrombectomy would be indicated if symptoms persist despite anticoagulation, reserving surgery if complications such as mesenteric ischaemia develop[5].

In splenic infarction associated with severe pancreatitis, the indication for anticoagulation is controversial and there is no consensus in the literature. No references have been found on how to proceed in cases of splenic infarction without thrombosis and with critical vascular stenosis in the context of a complication of severe pancreatitis.

In our case, we considered whether or not to anticoagulate the patient because the splenic infarction was associated with marked thrombocytosis without thrombosis. Given her age, we opted to use enoxaparin at prophylactic doses in order to avoid splenic thrombosis until the inflammation in the area improved or resolved, which would secondarily improve the splenic vascular stenosis. Subsequently, months later, after analytical and radiological control, the resolution of thrombocytosis and vascular stenosis was verified, and enoxaparin was discontinued.

In summary, the treatment of splenic infarction without thrombosis secondary to severe acute pancreatitis is a therapeutic challenge. The decision of whether or not to anticoagulate, the active ingredient to use and its dose, is currently undefined and highlights the need for clinical trials in order to establish clinical or consensus guidelines.

Descargar número completo

Descargar número completo Download full issue

Download full issue